Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea pursuant to Security

Council resolution 2060 (2012): Somalia

UN REPORTS: S/2013/413

12 July 2013

"Once Somalia adopts the EEZ under the UNCLOS regime, Somalia and Kenya would

be

required to initiate a separate process to negotiate a mutually acceptable

maritime boundary.

This would open the possibility of an adjustment of the maritime boundary from

its

perpendicular position towards a position following the line of latitude. Such

a shift would

effectively place some if not all of the disputed licenses mentioned above back

into Kenyan

waters. It is for this reason that on 8 October 2011 the Somali MPs voted down

attempts to

introduce an EEZ during the Roadmap process." UN Report, July 12, 2013.

Conflict between Somalia and Kenya over the maritime boundary

Somalia and Kenya have differing interpretations of their maritime boundary

and

associated offshore territorial rights. Currently, Somalia claims its maritime

boundary with

Kenya lies perpendicular to the coast, though this boundary is not enshrined in

a mutually

accepted agreement with Kenya, which envisages the maritime boundary as being

defined by

the line of latitude protruding from its boundary with Somalia.25

Map of disputed offshore zone between Somalia and Kenya, including positions of

Kenyan issued oil licenses.

The FGS has thus refused to recognise oil licenses granted to multinational

companies

by Kenya and which protrude into waters defined as Somali according to that

perpendicular

demarcation line. Oil multinational companies affected by the FGS opposition

have included

French oil company Total (Kenyan license L22), Italian major ENI (Kenyan

licenses L21, L23

and L24), US oil firm Anadarko (Kenyan license L5) and Norway’s majority

state-funded

Statoil26 (Kenyan license L26) (see again annex 5.5.k for a more detailed map of

disputed oil

licenses).

Corruption Risks Conflicts of interest surrounding the adoption of an Exclusive Economic Zone for

Somalia (EEZ).

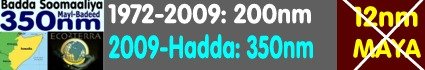

Since 1972, Somalia has claimed an extension of its territorial sea from 12

to

200 nautical miles. However, article 3 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on

the Law of

the Sea (UNCLOS) limits coastal States to claim a maximum territorial sea of 12

nautical miles

from the coast. Although Somalia signed UNCLOS in 1982, there has been

considerable

confusion over whether Somalia’s national legislation has been harmonised to

give recognition

to the UNCLOS regime.28 On 1 May 2013, however, President Hassan Sheikh issued a

statement announcing that the FGS has identified a 1988 law which puts Somalia

fully in

compliance with UNCLOS, and which would allow Somalia to implement an Exclusive

Economic Zone (EEZ), where territorial control would be limited to 12 nautical

miles but

where Somalia would continue to claim sovereign rights to explore, exploit,

conserve and

manage natural resources that exist within 200 nautical miles of its coast.

Once Somalia adopts the EEZ under the UNCLOS regime, Somalia and Kenya would

be

required to initiate a separate process to negotiate a mutually acceptable

maritime boundary.

This would open the possibility of an adjustment of the maritime boundary from

its

perpendicular position towards a position following the line of latitude.29 Such

a shift would

effectively place some if not all of the disputed licenses mentioned above back

into Kenyan

waters. It is for this reason that on 8 October 2011 the Somali MPs voted down

attempts to

introduce an EEZ during the Roadmap process.30 Once Somalia adopts the EEZ under the UNCLOS regime, Somalia and Kenya would

be

required to initiate a separate process to negotiate a mutually acceptable

maritime boundary.

This would open the possibility of an adjustment of the maritime boundary from

its

perpendicular position towards a position following the line of latitude.29 Such

a shift would

effectively place some if not all of the disputed licenses mentioned above back

into Kenyan

waters. It is for this reason that on 8 October 2011 the Somali MPs voted down

attempts to

introduce an EEZ during the Roadmap process.30 The Monitoring Group understands that Kenya suspended Norwegian oil company Statoil from block L26 in late 2012, as the company was unwilling to meet

financial

obligations of developing exploration activities in the block while legal

uncertainty prevailed

over the Kenyan-Somali maritime boundary.31 However, a Kenyan Government

official has

confirmed that Statoil has nevertheless expressed interest in returning to

develop L26 should

the maritime boundary dispute be resolved in favour of Kenya.32 The Monitoring Group has obtained information of attempts by the Norwegian

Government to influence Somali parliamentarians and other FGS officials to adopt

the EEZ for

Somalia, which, as explained above, would lead to a separate process of

redrawing of the

maritime boundary towards a line of latitude.

Norway has been involved in attempts to introduce the EEZ onto the

parliamentary

agenda since at least 2008, when former UN SRSG for Somalia Ahmedou Ould

Abdallah

initiated the preparation of preliminary information indicative of the outer

limits of the

continental shelf on Somalia. At the time this was conducted, Statoil had no

commercial

interest in Somalia.33 However, efforts by Norway to lobby Somali officials to

adopt the EEZ

now coincide with current Norwegian interest in the fate of L26 as well as with

Norwegian

involvement in the application of a Special Financing Facility (SFF) donor fund

of $30 million

which has been allocated under the management of FGS officials with a track

record of

corruption (see annex 5.2 on page 154 of the S/2013/413 UN Reports). (Note:

Annex 5.2: is about "Public financial mismanagement and corruption".) Norway has been involved in attempts to introduce the EEZ onto the

parliamentary

agenda since at least 2008, when former UN SRSG for Somalia Ahmedou Ould

Abdallah

initiated the preparation of preliminary information indicative of the outer

limits of the

continental shelf on Somalia. At the time this was conducted, Statoil had no

commercial

interest in Somalia.33 However, efforts by Norway to lobby Somali officials to

adopt the EEZ

now coincide with current Norwegian interest in the fate of L26 as well as with

Norwegian

involvement in the application of a Special Financing Facility (SFF) donor fund

of $30 million

which has been allocated under the management of FGS officials with a track

record of

corruption (see annex 5.2 on page 154 of the S/2013/413 UN Reports). (Note:

Annex 5.2: is about "Public financial mismanagement and corruption".) Indeed, between 6 and 13 April 2013, two non-governmental organisations, the

Oslo

Center and the National Democratic Institute, hosted several Somali MPs,

including the FGS

speaker of parliament and Norwegian national, Mohamed Osman Jawari, on a Study

Tour for

the Federal Parliament of Somalia, in Oslo. The week-long programme included a

briefing on

the SFF by Norway’s Special Envoy to Somalia, Jens Mjuagedal, and Senior

Advisor, Rina

Kristmoen, as well as a briefing on Norwegian legal assistance to Somalia for

the establishment

of an internationally-recognized EEZ. Former Norwegian oil minister Einar

Steensnaes also

briefed on the issue of management of natural resources (see annex 5.5.l. for

programme on page 170 of the UN S/2013/413 Report). (Note: Annex

5.5.l: is about "Programme of Study Tour of Somali MPs in Oslo 6 – 13 April 2013.")

In this way, Norway’s development assistance to Somalia may therefore be

used as a

cover for its commercial interests there. Norway’s Minister of International

Development, Heikki Eidsvol Holmås has, however, publicly denied any link between Norway’s

assistance to

Somalia in establishing its continental shelf rights and any commercial oil

interest.34

NORWAY Response to UN Report

July

19, 2013 Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs responding to UN Monitoring Group

Report said "Norway regrets claims by a UN report linking Norwegian

development efforts to commercial interests in Somalia." July

19, 2013 Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs responding to UN Monitoring Group

Report said "Norway regrets claims by a UN report linking Norwegian

development efforts to commercial interests in Somalia."

"Norway has for many years provided extensive assistance to Somalia both

humanitarian, as well as to support efforts for peace and reconciliation and for

reconstruction and development of a country who has suffered so much from

hungers and wars. This has been a consistent policy aiming towards a more stable

and peaceful Somalia, in which the Somali people may begin to enjoy security and

hopes for a more prosperous future.

It is therefore with serious concern that we understand the Monitoring Group in

its Report to the Security Council is conveying some conspiratory allegations,

found on the internet, implying that Norwegian assistance to Somalia is a cover

to promote the commercial interests of some Norwegian oil companies. This is

both unfounded and untrue."

Adding "We are aware that the Norwegian oil company Statoil has showed some

interest in possible future oil concessions in Kenya, but the Norwegian

Government has always advised the company not to apply for such concessions in

any areas where there may be a potential legal dispute, and when realizing that

this was the case with the mentioned L26 block, Statoil decided not to get

involved."

MORE AT Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website.

AKHRI: Waa Maxay Faraqa u Dhexeeya Dhul-badeedka (Territorial Sea) iyo Aagga

Dhaqaalaha (EEZ)?

__________

References:

25 Kenya claims that a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed with

Somalia’s TFG in April 2009 set the border running east along the line of latitude. However,

Somalia claims that the purpose of the MoU was not to demarcate the maritime boundary but rather to

grant non-objection to Kenya’s May 2009 submission of claim? to the UN Commission on the Limits of the

Continental Shelf to delineate the outer limits of Kenya’s continental shelf beyond the 200

nautical mile limit. (Each country’s claim requires proof of cooperation with its neighbors.) Since

it was not ratified by the parliament, Somalia claimed that the MoU did not, in fact, have legal basis.

Somalia’s parliament rejected this MoU in August 2009, claiming that Somalia was adhering

to the appropriate requirements for delimitation of the continental shelf – not

agreeing to a maritime boundary with Kenya. See Lesley Anne Warner, “East Africa’s Oil/Gas Rush

Highlights Kenya- Somalia Maritime Border Dispute”, available at

http://lesleyannewarner.wordpress.com/2012/07/21/east-africas-oilgas-rush-highlights-kenyasomalia-maritime-border-dispute/

. On the 6 June 2013, the Office of the Prime Minister in Somalia issued a statement saying that the council of ministers had decided that

The Federal Government of Somalia does not consider it appropriate to open new discussions

on maritime demarcation or limitations on the continental shelf with any parties.

26 See

http://www.statoil.com/annualreport2011/en/shareholderinformation/pages/majorshareholders.aspx

for precise statistics on Norwegian government holdings in Statoil.

28 See Thilo Neumann and Tim Rene Salomon, “Fishing in Troubled Waters –

Somalia’s Maritime

Zones and the Case for Reinterpretation”, Insights, American Society of

International Law,

15 March 2012.

29 According to a maritime lawyer interviewed by the Monitoring Group on 22

April 2013, should

Somali MPs vote for an EEZ, the boundary would be identified through a process

of negotiation

between the Somali and Kenyan Governments under international mediation, and

would likely shift

from a perpendicular position towards a position of latitude, given previous

precedent set in the East

African region, particularly in relation to the Tanzanian-Kenyan maritime

border.

30 See

http://www.garoweonline.com/artman2/publish/Somalia_27/Somalia_The_Roadmap_Gets_a_Tear_on_the_EEZ.shtml

.

31 Kenyan Energy ministry Permanent Secretary, Patrick Nyoike was quoted in the

financial press on

5 November 2012 as suggesting Statoil was relieved of L26 due to failing to

honour a 3-D seismic

development plan, see

http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Corporate-News/Kenya-expels-oil-giant-Statoil-from-exploration-plan-/-/539550/1612432/-/708r31z/-/index.html

. However, a Kenyan

Government official interviewed in April 2013, said he had been informed that

Statoil did not want

to take the risk of developing L26 while the maritime boundary was still in

legal dispute.

32 Interview , 12 May 2013.

33 See Norwegian Foreign Ministry website:

http://www.regjeringen.no/en/dep/ud/press/news/2009/shelf_assistance.html?id=555771

.

L26 was

negotiated in 2012, see

http://www.trademarksa.org/news/norwegian-firm-statoil-joins-search-oil-kenya

.

34 See

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a6d5d1b6-bd9f-11e2-a735-00144feab7de.html .

###END###

Waa Maxay Faraqa u

Dhexeeya Dhul-badeedka (Territorial Sea) iyo Aagga Dhaqaalaha (EEZ)?

REMEMBER: June 6, 2013: Somali Federal Government clarifies its position on

territorial waters

The government’s position is Somali Law No. 37 on the Territorial Sea and Ports,

signed on 10 September 1972, which defines Somali territorial sea as 200

nautical miles and continental shelf. On 24th July 1989 Somali ratified the UN

Convention on the Law of the Sea. Faahfaahin

Faafin: SomaliTalk.com | July 21, 2013

Baarlamaanka Soomaaliya oo si kulul uga dooday Sharciga Cusub ee

Kalluumaysiga iyo Xeerka Badda Soomaaliya ee Law No. 37

|