STIRRING THE SOMALI WATERS: TOWARD A MARITIME OIL WAR?

- Posted by Cassie Blombaum on 10 Jun 2013 in Africa, Business Risk, Elections,

Energy, Exploration, Kenya, Military Activity, Political Risk, Somalia, United

States

Source:

http://blog.inkerman.com

The never-ending maritime dispute between Somalia and Kenya is, by now, well

understood. Indeed, since 1972, the two countries have been lobbying the UN to

see their side of the ‘Indian Ocean’ story. Reports of possible pirate political

involvement aside, for the most part, this disagreement has only been a war of

words. Going forward, it remains to be seen whether the two nations will engage

in a full-scale violent confrontation over the hydrocarbon-rich sea. If such an

event were to pass, however, Kenya is believed to have the upper hand. Indeed,

Nairobi has already secured enough powerful allies, including Norway, France,

and the US (all of which have stake in the Kenyan-authorised offshore oil

blocks), that would conceivably make a Kenyan victory a ‘sure thing’ from the

start.

For many armchair analysts, East Africa appears to have enough problems. Plagued

by pirates riding the waves of the Indian Ocean, and bullied by al Qaeda-linked

al Shabaab militants that threaten the very foundation of Somalia, the region

has been a constant focal point for insecurity. To be fair,

the pirates are

starting to let up. Moreover, the latest reports paint a picture of an

al

Shabaab on the decline – at least for now. However, a looming fight over oil and

gas could threaten to undue any transition toward stability in the region,

particularly when it comes to Somalia’s relationship with Kenya. Setting the Scene For Trouble

The latest East African scandal began with a seemingly innocuous clarification

by the Somali Government. Amid a weekly council of ministers gathering on 06

June 2013, officials decided to embark on the contentious topic of Somalia’s

maritime borders. By meeting’s end, the ministers had agreed to make “null and

void” the 2009 maritime borders Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Kenya

and Somalia’s now-defunct Transitional Federal Government (TFG). Adding fuel to

the fire, the Somali Government, led by President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud,

officially ‘extended’ the country’s sea territory by 200 nautical miles, and

also defined the continental shelf as part of its maritime boundary.

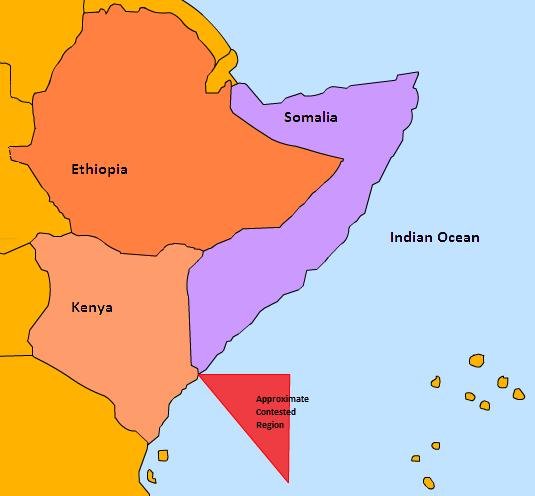

To the outside observer, this move may seem like a trivial declaration. Indeed,

Somalia and Kenya have been fighting over this very issue since 1972. However,

when given the fact that those 200 extra nautical miles could lead Somalia to

join the Indian Ocean hydrocarbon bonanza and simultaneously pit Nairobi and

Mogadishu in a fight over potentially lucrative reserves, this announcement is

far more consequential. Boundary Bickering So what, exactly, is the 2009 MOU? And better yet, why is Somalia keen on

supposedly ‘expanding’ its maritime boundaries? Whilst the general theme of the

MOU revolves around the issue of nation’s contested maritime borders, the exact

details and ultimate outcome of the memorandum

depends on which country you ask. For Kenya, the MOU had settled matters once and for all. Nairobi officials

believe that the April 2009 agreement signed by then-Kenyan Foreign Affairs

Minister Moses Wetangula, and his former Somali counterpart, Abdirahman Warsame,

allowed Kenya – not Somalia – to officially demarcate its maritime borders to

include the approximately 200 nautical miles off the coast of the Horn of

Africa. More precisely, for Nairobi authorities, the MOU extended the Kenyan

boundary east to approximately the 45° line of latitude. Naturally, Somali authorities offer a different view of the MOU signing. For

them, the memorandum only amounted to Mogadishu giving the “O.K.” for Kenyan

authorities to submit their version of the East African map. In other words,

Somalia sees the MOU as simply an ‘agree to disagree’ document. In Somalia’s

defence, this argument is not out of line, given that in order for a country to

officially submit its boundary map to the UN Commission on the Limits of the

Continental Shelf, it must provide proof that it has “cooperated with its

neighbours”. For Somalia, then, this document is only proof that it ried to

‘cooperate’. In the end, however, the Somali parliament rejected Kenya’s views

on the Indian Ocean boundaries in August of 2009; and the East African

neighbours have been squabbling over a body of water roughly 23,600 miles in

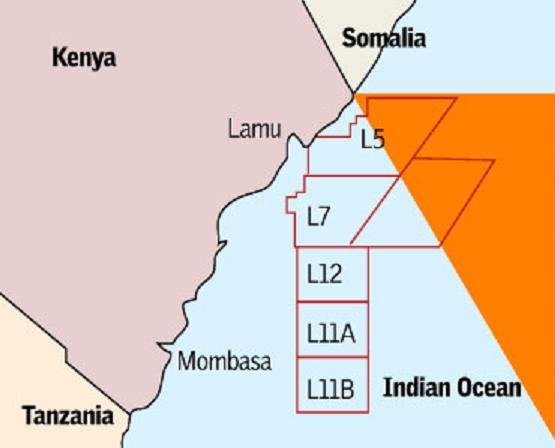

area ever since. Joining the Hydrocarbon Bonanza For Somalia, the fight over the maritime demarcation goes far deeper than a

quest for seaside riches. It is also a matter of pride. The view among many

Somalis is that their country has been taken advantage of, not only by Kenya,

but by international firms which they have accused of capitalising on their

decades-long lack of central government for their own financial gain. When Kenya

authorised another round of oil contracts in

July 2012, this time to include the

disputed Eni-controlled L21, L23, and L24 blocks, Somali authorities were quick

to cry ‘imperialism’. In particular, an angered Abdillahi Mohamud, who manages

the East African Energy Forum, claimed that these oil blocks, as well as the

Total S.A-controlled L22, the Anadarko Petroleum Corporation-bought L5, and

Statoil-run L26, were all sold off “illegally” by Kenyan authorities. Noted

Mohamud: “These offshore oil blocks are solely owned by the Republic of Somalia

as stipulated in the 1982 UN Common Law on the Sea (UNCLOS). Kenya’s move to

sell these oil blocks violates international law”. Indeed, for a country which

only recently managed to achieve a presidential election following decades of

bloodshed, Kenya’s oil block sell-off was not exactly a morale-booster.

Pride aside, the financial ramifications of the border demarcation is clearly of

importance as well. Whilst the exact amount of hydrocarbon reserves in the

23,000 square miles of water remains unknown, some reports have estimated that,

when combined with its reported onshore reserves, Somalia could have as much as

110 billion barrels of oil. With regard to offshore gas, in total the East

African region is believed to have

440 trillion cubic feet of recoverable

reserves. Clearly any slight ‘cheat of hand’ with regard to the Somali

boundaries with Kenya could spell billions of dollars in lost revenue for the

fledgling government in Mogadishu. The Way Ahead The never-ending maritime dispute between Somalia and Kenya is, by now, well

understood. Indeed, since 1972, the two countries have been lobbying the UN to

see their side of the ‘Indian Ocean’ story. Reports of possible pirate political

involvement aside, for the most part, this disagreement has only been a war of

words. Going forward, it remains to be seen whether the two nations will engage

in a full-scale violent confrontation over the hydrocarbon-rich sea. If such an

event were to pass, however, Kenya is believed to have the upper hand. Indeed,

Nairobi has already secured enough powerful allies, including Norway, France,

and the US (all of which have stake in the Kenyan-authorised offshore oil

blocks), that would conceivably make a Kenyan victory a ‘sure thing’ from the

start. This is not to say, however, that the Somali Government will not try to change

the Kenya-as-East African-powerhouse narrative. To be sure, in 2012, the Somalia

Government went ahead and announced that it, too, would auction approximately

“308 newly delineated oil blocks”, without seeking a cooperation agreement with

Kenya. Of course Somalia does not want to anger its neighbour. In their weekly

meeting on 06 June 2013, cautious ministers did state that, whilst they would

seek to implement changes to their national territory, they are looking

“forward” to working with Kenya, and “the government of President [Uhuru]

Kenyatta Kenyatta”.

http://blog.inkerman.com/index.php/2013/06/10/stirring-the-somalia-waters-toward-a-maritime-oil-war/

Source:

http://blog.inkerman.com

Faafin: SomaliTalk.com | June 11, 2013

|