The military offensive against Islamic al-Shabaab fighters is gearing up for an assault on Kismayo that’s seen as a key element in a dispute over oil and gas.

MOGADISHU, Somalia, Aug. 3, 2012 (UPI) — The military offensive by Kenyan and Ethiopian forces against Islamic al-Shabaab fighters is gearing up for an assault on the Indian Ocean port of Kismayo that’s increasingly seen as a key element in a brewing dispute over oil and natural gas.

Kismayo, in southern Somalia near the Kenyan border, is al-Shabaab’s most important base, through which it gets its supply of weapons and much of its revenue.

But the strategic value of the city, one of Somalia’s three deep-water ports, has swelled in recent months because of the huge oil and gas discoveries off East Africa.

Kenya made its first big strike in March and the discoveries, all the way south to Mozambique, are piling up. Even South Africa is undertaking major seismic testing, hoping to join the region’s growing energy boom.

The oil and gas strikes, including some in neighboring Ethiopia, a U.S. ally that’s played a prominent role in the 6-year-old war against the Somali Islamists, have raised the strategic context of the conflict to a new level.

On July 6, the Western-backed Transitional Federal Government in Mogadishu, Somalia’s war-battered capital, accused neighboring Kenya of illegally awarding offshore oil and gas exploration rights to leading European oil companies in waters claimed by Somalia.

Eni of Italy got three blocks and Total of France got one.

Kenya and Ethiopia, encouraged by the United States, deployed armored columns into Somalia from the south and west in late 2011 to aid the beleaguered TFG crush the Islamists. In recent months, they have pushed al-Shabaab into a southwestern pocket, with Kismayo as its main stronghold.

The dispute over the four exploration blocks is likely to complicate the stampede of oil companies into a region that over the last year or so has become one of the world’s hottest energy prospects.

Analyst Jen Alic, reporting for energy Web site OilPrice.com, observed July 15 that Kenya’s timing “will be viewed as suspicious in Somalia …

“It’s plausible that Kenya was hoping that its very successful assistance in pushing al-Shabaab out of Mogadishu and a number of other key bases and strongholds would give it carte blanche to act on oil exploration in contested coastal waters.”

It’s a tricky situation that goes beyond the legal aspects on ownership of these waters.

“Kenya’s involvement in southern Somalia was designed to gain the upper hand on offshore oil block concessions that rightfully belong to Somalia as stipulated in the 1982 U.N. Law of the Seas convention,” said Abdillahi Mohamud, director of the East African Energy Forum.

That’s an international lobby group that seeks to protect Somalia’s energy assets from being exploited by other states.

That’s an international lobby group that seeks to protect Somalia’s energy assets from being exploited by other states.

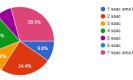

The forum estimates that impoverished Somalia, ravaged by clan warfare since the dictatorship of Siad Mohammed Barre was toppled in 1992, has offshore and onshore oil reserves of 80 billion-100 billion barrels.

“This small nation of 10 million stands to have the fifth largest petroleum reserves in the world, eclipsing heavyweights like the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Nigeria,” Mohamud noted.

That may well be an overly optimistic estimation. But there’s little doubt that the volume of oil and natural gas in the region is vast.

The recoverable gas reserves found off Tanzania and Mozambique since 2010 are estimated to total 100 trillion cubic feet. Exploration companies say the true figure may be more than double that.

The U.S. Geological Survey says East Africa’s waters hold more than 440 tcf of recoverable gas reserves, which will transform the region into one of the world’s leading gas exporters, primarily to energy-hungry Asia.

The danger is, of course, that the oil and gas strikes off Somalia will end up fueling the Somali conflict, if they haven’t already, and possibly even widening it as regional powers vie with each other to control the energy riches.

This could apply to other East African states as well. Ethiopia, for instance, is considered to be sitting on considerable energy reserves.

These looks set to inflame a long-running insurgency against the brutal regime of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, who took power in 1991 and who is now reported to be in poor health.

Oil discoveries in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a treasure house of mineral riches, are adding fuel to a murderous war waged largely by neighboring states over its resources.

Source: http://www.upi.com/

Somalia Lays Claim to Kenyan Offshore Oil Blocks

Somalia has claimed that Kenya was not allowed to award four deepwater blocks to oil companies Total and Eni because the area lies in Somali waters. It is unlikely that a long-term solution will be found to the dispute because of the uncertainty of Somali politics.

The Somali government has accused Kenya of awarding offshore oil and gas blocks illegally to Total and Eni, with Somalia claiming that the blocks lie in Somali waters. On Friday (6 July) Somali deputy energy minister Abdullahi Dool claimed that the four deepwater blocks were invalid and that the East African war-torn country will take the matter to the UN. The four blocks were amongst the seven awarded recently by the Kenyan government–three to Italy’s Eni and one to French firm Total (see World Markets Energy : Kenya: 3 July 2012:and World Markets Energy : Kenya: 17 May 2012:). The blocks in question are L21, 22, 23, and 24 in the Lamu Basin.

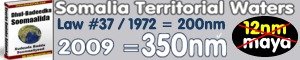

Kenya rejected the Somali claims and upheld its rights to the area, which has long been contested by the two countries. The situation is compounded by the fact that the maritime border has never been adequately delineated. Kenya claims that the border runs east from the point at which the land border meets the offshore–similar to the maritime boundaries of other countries along the coast. In contrast, Somalia claims that the boundary should extend perpendicular to the coastline, giving it a large chunk of the waters claimed by Kenya.

Although the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding in 2009, which stated that the border should run east long the line of latitude, Somalia rejected the agreement and the lack of an effective central government in the country does not help matters. Furthermore, no legal boundary can be established until both governments sign a UN-approved agreement or move the issue to an international court.

The situation for Kenya is slightly worse because the border dispute prevents it from extending its claim to the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, and this prevents the government from awarding more licenses.

The situation is not unique. On the other side of the continent, both Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire have long been embroiled in maritime border disputes that affect offshore hydrocarbon exploration. Africa’s borders were drawn up during colonial times and are often not formally recognized–by both the international legal community and the parties involved. DRCongo has been accusing Angola of “stealing” oil from offshore wells near its coast–thought to be a reference to operations in the Cabinda enclave, which is surrounded by DRCongo and Congo.

An agreement on the joint exploitation of offshore resources was reached in 2007, but apparently not implemented. In early 2010, Angola’s National Assembly agreed to open talks with the DRCongo on the extension of its border out to 350 nautical miles, rather than 200 miles, as a prelude to an application to the UN for recognition of that boundary. Relations between the countries deteriorated sharply in 2011 after a series of disputes. This particular dispute has prevented exploration from progressing as foreign companies are unwilling to take up exploration block in a potentially oil-rich area due to the uncertainty. With regards to the Ghana- Cote d’Ivoire dispute, matters seem less tense, although a definite outcome has not yet emerged.

In 2011, the Ivorian authorities–at the time still under the helm of former president Laurent Gbagbo–published a map with a new border, taking in several Ghanaian oil blocks (see World Markets Energy : Cote d’Ivoire: 28 October 2011:). The situation caused a stir in Ghana, as the proposed border came dangerously close to the Jubilee oilfield and recent oil and gas discoveries such as Tullow’s Tweneboa and Enyenra complex. However, the governments have enjoyed cordial relations for a long time and are keen to solve the matter peacefully.

Outlook and Implications

In contrast to Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, the border dispute between Somalia and Kenya may take several years to resolve. Although Kenya and Somalia have had positive diplomatic relations despite the border dispute, the very nature of Somali politics will mean that coming to a resolution will be challenging. It has always been difficult to negotiate on such matters with Somalia, as there is no central authority that can make decisions on high-level international matters.

The discovery of oil onshore Kenya–while offshore exploration is also taking off thanks to the successes further down the East African coast–has re-ignited this border dispute. Of importance is the impact that this dispute will have on exploration. Although neither Eni nor Total are likely to start exploration immediately, it is vital that the dispute is settled. In the event of a discovery, operators will suffer further uncertainty over which side should receive revenues. Martin Heya, Kenya’s petroleum commissioner said in April that companies will be unable to drill in their respective blocks until the boundary is settled.

Furthermore, looking at the Ghana-Cote d’Ivoire dispute, it is clear that international legal assistance will not be forthcoming soon as claims lodged at the UN can take years to settle. In the case of the West African states, UN proceedings were unsuccessful and the countries have now been left to their own devices, trying to negotiate a solution between themselves. This would hardly be the ideal solution in the Kenya-Somalia case, as negotiating with an uncertain Somali political force is unlikely to be successful, and if it is, the “solution” will not be long term due to the unstable nature of Somali politics.

Source: http://www.rigzone.com/

*

ASCWW.

Walaalayaal waxaan ilaa iyo hadda fahmi weysanahey maslaxadeena runta ah.

Macnaa inaan isu kaashano wixii danteena guud iyo tan mustaqbalkeena faa’iido u leh.

Gaar inaan fahano inaan u baahanahey oo keliya RABBI (SW), oo aynaan u baahneyn gaal & munaafiqiin daneystayaal ah oo maanta muran geliyey badeena & berigeena ama dhulkeena.

Mustaqbal caruurteena haddii aan u fekereyno waa inaan hurdada ama suuxdinta ka kacno, oo aan damiir isu yeelno lana maxkamadeeyo tuugadaas weli ku jirta siyaasada, oo qeyb ka ahaa in dood ama muran la geliyo hantideena.

Waxaanan ku gaari karnaa in laga xoroobo sanamyada cusub “qabiil, goboleysi”,.

Waana RABBI (SW) loo soo laabto, lana bilaabo talaabo aan ku hananeyno mustaqbalkeena.

WCSWW.