Regionalism and Alternative Forms of Governance:

A Critique on Centralized, Top Down Approach to the Problem of Somalia

It is often counter intuitive and very difficult for many scholars, policy makers, journalist and even politicians to explain or make sense of the collapse of the former Somalia. Many others fail to explain the prolonged socio-political conflict in the most homogenous nations in the African continent. However a close examination of Somali social groups reveals that Somalia is a complex dynamic organism of a system of self organizing assorted groupings. The Somali problem can be reduced (at least conceptually) to a problem of complexity that involves “competition and coordination” by the groups, which could result in order and/or disorder. It is a paradigm in which the the clans either compete for governing the state ( in the case of Mogadishu or Southern Somalia) or establish a convention to govern the states through agreed system (in case of peaceful northern quasi-independent states of Somaliland and Puntland).

Equally, the current state of affairs in Somalia can be put in plain words as a contingent outcome of a dynamic and complex socio-political system; a system that consists of self-regulating, competing entities that endogenously organize into diverse groups and regional polities. While the Somalia as whole may depict a sad picture of human failure and socio-political collapse, yet a deeper look of at a finer scale would show the existence of vibrant and stable regional governments/polities amidst the disorder that is Somalia. These stable regional polities embody a rich source of alternative routes to stabilizing the rest of what use to be Somalia; a model for resolving conflict and additional tool or at least an experience for the international community.

Amongst the most elemental driver of regional stability and collective coordination is the Somalia clan norms and the clan system. The Somali clan system – and its modern manifestation as regionalism – is an established convention complete with a social structure, laws, administrative rules and well defined social norms for social interaction. It is also in essence the most reliable meta-institution through which the Somali people conduct their affairs. Through the clan system Somali people organize and regulate all aspects of social life within and between clans. They employ hybrid of modern social techniques and local customary laws that function as mechanisms for clan self preservation, inter-clan cooperation and conflict resolution and generally as a guide for interaction between clans and within each clan and even formation of traditional regional polities.

Historically the clan system enabled Somali people to form their own independent governing structures or even their own traditional states. Historical or traditional polities are outcomes of highly complex co-evolution of clan system’s , social norms and pastoral society. This an evolutionary process however must have been unequal in the areas inhabited by Somali people. For instance, recorded evidence that some areas in Somalia had a very advanced governing structures (Sultanates / Kingdoms in Obbio, Hafun, Taleeh, Hadaftimo and Hargeisa) while other areas remained less developed or under Arab Sultanates. (Some of these are mentioned in Luigi Bricchetti Robecchi’s Journeys in the Somali Country 1890-91 ). Today however, there is empirical evidence of similar patterns of emergence of traditional polities in the nation that was Somali Democratic Republic. (e.g. Puntland and Somaliland).

The emergence of alternative polities in Puntland and Somaliland after the collapse of Somalia is very important to understand. Both Puntland and Somaliland constitute the re-emergence of traditional independent (or quasi independent states) in contemporary Somalia. This does not mean that I particularly support or justify the legitimacy of any but a mere practical truth on the ground one that must be understood for what it is and even used to foster stability in southern Somalia.

Today’s regional authorities or regional polities are based on collective conventions and pacts achieved through clan systems. They also offer diverse and alternative institutional arrangements to cope with the failure of the former Somali Democratic Republic. However to make use of any diversity of institutions , one must disect, understand analyze and attempt to replicate the process that leads groups to organize and eventual formation of regional polities.

It is equally important to acknowledge that these two northern states came to being and continue to exist practically with no support from the international community. (This is particularly true in case of Puntland). On the other hand, the international community, (primarily the UN) spent an enormous effort and material in constituting a central government for the entire country that was Somalia. Many of these attempts failed and the last attempt to constitute a central authority for Somalia is on life support.

Puntland and Somaliland, for instance, employed diverse institutional arrangements, that included civic organizations, former security forces, intellectuals, extensive of clan based discussions (led by traditional clan elders) to form a collective pact to govern their affairs. This created Puntland in 1998 and Somaliland earlier in 1992.

Though not conclusive, there is compelling evidence that it is highly likely that today’s Puntland (and to some extent Somaliland) are historical outcomes or contingencies of the local traditions to self-governance that predate modern day Somalia. Today’s Puntland for instance is made of several traditional sultanates that existed in the area prior to the colonial era. It is this long tradition of self reliance and local administration that enabled these regions to constitute functional authorities. It certainly is not random chance that the both Puntland and Somaliland have emerged while many other peaceful remained trapped and eventually consumed by the Somali Civil War.

As in the pre-colonial era, the success of “clan sanctioned agreements” have become empirical reality and a solid ground that can ascertain a respected representative authority; indeed clan sanctioned agreements are empirically grounded accomplishments that endogenously bring people together – just as it were in the pre-colonial era but perhaps with a modern twist of quasi-state entity. Both Somaliland and Puntland are exemplary “empirical evidence” of how an authority is distributed to sub-clans through a bottom up functional organs nominated by the clan orders or projected by them.

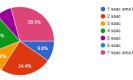

The Somaliland and Puntland experiments are in sharp contrast to the “4.5 power sharing plan” of the TFG, in which a distant “arm chair intellectuals” designed a power sharing scheme to distribute power to Somalia’s clans without the participation of local clan members, elders, regardless of the reality on the ground or the local metaphors. Of course, the UN and many policy analyst would claim that the “4.5 power sharing plan” is a clan neutral and attempt to justify it as fair means to distribute power to the Somali clans.

The fact is however that the pre-conceived notion of fairness is one that is exogenously imposed or at least is perceived as imposed solutions (not endogenously derived as in case of Puntland). The perception of imposed rule (whether fair or not) affects the expectations as well as the behavior of Somali clans. Why would Somaliland or Puntland would want exchange whatever relative peace and prosperity for a future possible prosperous Somali nation state. It is these institutional and cultural factors that must be understood by the international community and Somalia enthusiasts. Somalia does not need prescriptive paternalism or policy designed at far away places by all well meaning elitist westerners or for that matter any non-Somali; A local Somali solution is more likely to succeed than any other prearranged solutions to create central authority.

The world renowned public policy expert Dr Elinor Ostrom after extensive empirical studies suggested that policy analysis and policy design In the 21st be broadened to include a greater attention for regional and local governments. She also has pioneered the concept of institutional diversity in policy analysis to align centralized policy making with empirical realities of human choice and evolution of choices. In fact institutional diversity enables policy makers, decision makers and policy analysts to find solutions for complex problems from more than one source.

Understanding this clan driven , real Somali regional dynamics is fundamental because most important decisions related to regional security, regional development, and the possibility of reconstituting a nation state for the former Somalia would demand participation and interaction of all local stakeholders.

Moreover, the quasi-independent regional polities such as Somaliland and Puntland provide “alternative mechanisms” as well as “socially acceptable policy prescription” to Somalia’s problem. They also represent examples of a distinctly successful normative policy approaches available to those engaged in helping Somalia end its long civil conflict.

Employing diverse approaches or diverse institutional arrangements is perhaps one way to manage the complexity that is Somalia, to cope with uncertainty and facilitate coordination of diverse actors. Employing expanded search for solutions that includes using the alternative institutions, direct involvement and consultation with Puntland and Somaliland can only help the idea of reconstituting a Somali nation-state. To that end, the International community must acknowledge and position it self to deal with various regional institutions including the quasi independent state of Puntland and Somaliland.

If metaphors are the concepts we use to understand one thing in terms of another, the world community must acknowledge the local metaphors; local preferences, respect the choice of the regional groups without affirming the dissolution of the state. The United Nations and United States must not treat any potential central authority such as TFG to be the only option for stable and prosperous Somali peninsula. Instead the international community must consider diverse contingencies each of which could possibly lead to credible resolution to the Somali problem. In doing so however, the international community in general must pay a close attention to local preferences, existing intuitions/ governments and most of all local metaphors.

Finally, because metaphors and narratives play an important role in public opinion and hence behavior, effectiveness of policy and implementation of policies; It is extremely important that policy designers create action and policy through language based on local metaphors that focus on viable and stable regions of the Somali peninsula rather than ambitious plans of creating strong central authority or restoring a Somali nation-state without local mandate.

Abdul Ahmed III

abdul.ahmed@asu.edu

.

Abdul Ahmed III is a policy modeling specialist; he contributes to research institutions in Arizona, Washington DC and Virginia.

This is Real Somalia 101.

If only it could be read by all those who are involved with the remaking of Somalia.

Thanks

AK

this is good alternative model, the policy makers should consider and give special attention to this atractive opinion.

Thanks Abdul