THE MYSTERIOUS DEATH OF ILARIA ALPI

By: Michael Maren

Email: michaelm@mail.ixpres.com

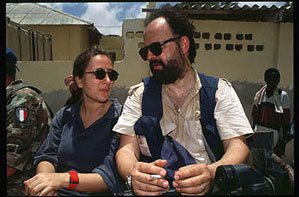

Ilaria Alpi and Miran Hrovatin, a few days before they were

slain in Mogadishu, on March 19, 1994 (Source:

http://www.raffaeleciriello.com)

Part I: Forty five minutes after I first met Ilaria Alpi, she was dead...

Daawo Aljazeera

Some people say she had information about the Italian military selling guns

to the warlords. Some say she had information about the torture and killing of

Somali prisoners by Italian soldiers. What I know is this: Forty five minutes

after I first met Ilaria Alpi, she was dead, slumped in a puddle of her own

blood in the back seat of a white Toyota pickup truck. We had spoken briefly

inside the high-walled compound of the Sahafi hotel, the journalists' hotel, in

Mogadishu. She told me she was a television correspondent from Italy and had

just returned from a town in northern Somalia, a place she heard I knew well.

But Ilaria had no need to introduce herself; I already knew of her. She stood

out in Mogadishu. She was a small, serious 32-year old Italian reporter who

fearlessly stuck her microphone in the faces of UN officials, military

commanders and Somali warlords. While a lot of TV reporters spent more time

fixing their hair than studying the country, Ilaria made her name by working the

streets, using fluent Arabic and stubborn resolve to dig into places that few

other journalists saw.

Ilaria asked me if I'd have a free moment to talk that evening. She seemed shy,

almost apologetic about imposing on my time. I assured her that it was no

problem, and that I'd be willing to talk with her whenever she wanted, even

immediately if it would help. She couldn't talk right then, she said. There was

someplace she needed to be.

I collected my crew, the driver and two armed bodyguards who shadowed me every

moment I was outside the hotel compound, and we headed off to the northern part

of the city. Ilaria and her cameraman, Miran Hrovatin, climbed into their Toyota

pickup with a driver and gunman and also drove north. It was a quiet Sunday

afternoon in Somalia, just after lunch when a blanket of midday heat keeps the

sandy rubble-strewn streets of Mogadishu empty and menacing. I set off on my

rounds, trolling for stories and information. To that end I dropped in at the

home of a Somali friend, a young former guerrilla fighter who from time to time

passed along some valuable intelligence. On this particular day he didn't have

much to offer. His sister served us tea in the shade and we were relaxing,

talking about nothing of consequence, when we heard the short bursts of gunfire.

We kept silent for a moment, listening to hear if the shooting was going to

escalate. But nothing more happened, and we didn't give it another thought.

It wasn't until early evening when I returned to the Sahafi that I heard the

news. "It's Ilaria," my friend Carlos Mavroleon said to me as I walked into the

lobby. "They've killed Ilaria."

Carlos, who was working as a cameraman for ABC News, had run to the scene as

soon as he heard the gunfire. He learned that a Land Rover full of gunmen had

cut in front of Ilaria's pickup in North Mogadishu. Someone started shooting.

Their driver and bodyguard were unhurt. Carlos took me upstairs to his hotel

room and showed me what he had videotaped at the scene. In the video, the bodies

are being removed from the pickup truck and placed in a Land Cruiser owned by an

Italian resident of Mogadishu, a man who was known to everyone by his first

name, Giancarlo. Ilaria is wearing bright orange pants, and Birkenstock sandals.

Her loose white shirt is stained with blood, and there is more blood smeared

across her forehead and on her blond hair. In the back of the Land Cruiser

Ilaria looks like she is sleeping. One of the Somalis who helped move the bodies

hands Ilaria's notebook and a pair of two-way radios to Giancarlo. And Giancarlo

says simply, that Ilaria and Miran were somewhere they shouldn't have been.

I knew what we were going to do later that night. I was used to the ritual by

now. We gathered, about ten of us, in someone's hotel room and poured tall

glasses of whiskey, the sickened pallor of our faces exaggerated by the wash of

fluorescent light reflected off chalky white walls. We sat until morning

exchanging bits of information that we hoped would add up to a reason, some

determination about why our colleagues were dead. It was important that each of

us believe that reasons existed. Ascribing a logic to death meant that measures

could be taken to avoid it. We could convince ourselves that hiring the right

security guards, driving on the right roads at the right times and saying the

right things would keep us safe. But we knew better.

There was no mystery to death here. We spent our days with hired bodyguards

travelling bombed out streets jammed with technicals - armed vehicles carrying

hungry, glassy-eyed teenagers with automatic weapons. Any one of those kids

could turn and pop you in a second, as easily as he could spit. Not even the

walls of the hotel provided real protection. One reporter was shot in the leg

during lunch. Another stepped from the shower just as a round sailed through the

concrete outer wall and exploded through the porcelain stall.

But that didn't stop us from looking for reasons behind Ilaria's death. There

was talk that she may have once fired a bodyguard who had then taken revenge.

That sort of thing happened a lot in Mogadishu. There was no faster way to die

here than to interfere with someone's livelihood. One of us even suggested that

Ilaria could have uncovered some information that threatened one of the warlords

or other powerful people. That was a nice thought. Given the choice, any of us

would have picked assassination by evil international gunrunners to death at the

whim of a bored teenager.

I participated in the discussion without ever believing her death was more than

really bad luck. Ilaria wasn't the first journalist to die in Somalia and she

wouldn't be the last. And after 15 years of covering stories in Africa I had

lost what little patience I had for conspiracy theories. All it takes is a few

missing pieces of information or inconsistencies in a large and complex story

for someone to start talking about the CIA or Mossad or the hand of unnamed

international forces.

Certainly there were mysteries surrounding Ilaria's death: Several of her

notebooks disappeared after her body was loaded on a plane for Rome. A 35mm

camera she had with her was also missing. But that alone was no reason to

believe in a conspiracy. Things do get misplaced. Every loose end can't be tied

up. And, after all, this was Somalia.

Somalia had been in a state of anarchy since 1991 when its dictator of two

decades, Mohamed Siad Barre, was defeated by rebel armies led by Mohamed Farah

Aidid. When Aidid's troops poured into Mogadishu, Barre's armies retreated south

and west from Mogadishu toward the Kenya border. As they fled, they destroyed

the country's food supply, burning fields and looting grain stores to slow the

pursuit of Aidid's rebels. By the time they were done, there wasn't much food

left in southern Somalia. The capital, Mogadishu, was reduced to rubble, and the

country's grain producing area was overrun by unruly militias. The aid groups

who came in from the West couldn't operate, and starvation began to spread. In

the summer of 1992, people in Europe and the U.S. began seeing the pictures of

starving Somali kids that resulted in Operation Restore Hope and the U.S.

Marines landing on the beaches of Mogadishu in December of 1992.

By January of 1993, a multinational task force had pretty much put an end to

what was left of the famine. But then they found themselves facing a much more

difficult problem: the heavily armed and uncompromising militias of Somalia's

warlords. A confrontation was inevitable. In June of 1993, the famous and

ill-fated hunt for Aidid began. It ended four months later, on October 3, 1993,

when 18 Americans were killed and the body of one of them was videotaped as it

was hog-tied and dragged through the dusty streets of Mogadishu.

By March of 1994 Restore Hope was over. Western peacekeeping troops were packing

their bags and leaving the unfinished job in the hands of darker-skinned

soldiers from Malaysia, India, and Pakistan. The press came in to cover that

retreat. Ilaria Alpi was among them. She was there to report on the withdrawal

of Italian troops when she died on March 21, 1994.

Over the next few years I thought about Ilaria from time to time. Usually it was

during a trip to Mogadishu when I would stop at the place on the road where she

was killed. There were many such places scattered throughout Mogadishu, where

friends and colleagues had lost their lives: the spot where

photographer

Dan Eldon was beaten to death by an angry mob; the intersection where Kai

Lincoln, a young U.N. worker, was gunned down by bandits. I had only met Ilaria

once, and briefly, and yet her death had stuck with me. I pointed out the spot

where she died to several people who had never known her. In my mind I would

trace the route of her pick-up down the hill. I would see the point where the

blue Land Rover cut them off on the road, where the gunmen piled out. I almost

thought I could see the tire marks left over when Ilaria's driver slammed the

truck into reverse trying to back away.

In the Summer of 1997, I saw wire reports about photographs that were published

in the Italian magazine Panorama. One photo shows Italian soldiers attaching

electrodes to the testicles of a Somali prisoner who is tied to the ground. In

another, a Somali woman is being raped with the end of a flare gun. The photos

were taken by the Italian soldiers themselves, peacekeepers recording their

triumph for posterity.

I began following the story. The publication of the photos forced the Italian

government to launch an inquiry. And that inquiry led to a diary kept by an

Italian policeman stationed in Somalia. (In Italy the police overlap with the

military.) The policeman, Francisco Aloi, wrote of spending time with a young

television journalist named Ilaria Alpi. He wrote about how Ilaria had

discovered some of the abuses and had gone to the Italian commander in Somalia,

General Bruno Loi and told him that she would expose the abuses if he didn't do

something about it. The general reportedly told Ilaria that it was only a few

isolated cases that he would investigate and pursue. Months later, as the last

Italian troops were leaving Somalia, the crimes remained uninvestigated and

perpetrators remained unpunished. And Ilaria was preparing to do her final

report from Somalia.

I learned that the controversy about Ilaria's death had never quite died in

Italy. In fact, the few loose ends that I was aware of had unraveled into a vast

tangle of conspiracy theories. According to various scenarios, Ilaria was

murdered because she had information about arms trafficking, toxic waste

dumping, or the selling of Somali children into slavery. All of these conspiracy

theories contained a common element: While the men who pulled the triggers were

Somali, the people who paid them, the ones who wanted Ilaria dead, were Italian.

Chief among the conspiracy theorists was Giorgio Alpi, Ilaria's father, a

well-known doctor in Rome, and member of Italy's communist party. In the four

years since Ilaria's death, he had appeared on Italian television, lobbied

journalists, and had done everything he possibly could to keep stories of Ilaria

alive.

In January of 1998, in an attempt to mollify Giorgio Alpi and close the book on

the rampant rumors, a group of Somalis were escorted to Rome to give depositions

against soldiers who were accused of torture. And when one of those Somalis - a

young man named Hashi Omar Hassan - showed up at the police station he was

arrested, charged with Ilaria's murder. It appeared to me that the Italians had

taken their two outstanding issues in Somalia and tied them up in one neat

package which they were prepared to flush away. The complete saga was reduced to

this: The young Somali, Hashi Omar Hassan, had been tortured by Italian troops

and then gotten his revenge by participating in the killing an Italian reporter.

End of story.

But none of that made much sense to me or fit with the facts I had collected

right after Ilaria's killing or what I knew about Somalia. It looked very much

like a coverup and, as in other well-known cases, the coverup was the most

powerful explicit evidence of the existence of the crime. And so I went to Rome

to take a closer look at the investigation and several things became clear to me

for the first time: Ilaria's death was not an act of random violence on a

Mogadishu street. Somebody wanted her dead. And she wasn't killed in midst of a

wild gun battle. She was assassinated, killed by a single shot fired from point

blank into the back of her head.

Part II: Conspiracy Theories

There are many details about his daughter's death that four years later continue

to keep Giorgio Alpi awake at night. There is the fact that no investigation was

ever done at the crime scene. And then there was the Italian military's refusal

to rush medical assistance to Ilaria after she was shot. And it breaks his heart

that incompetent forensic work has required that her body be exhumed, twice. But

the thing that angers him most is that he and his wife Luciana never really said

goodbye to Ilaria. When her body arrived back in Rome the family was told that

during the ambush she had been raked with automatic weapons fire. They decided

they didn't want to see her like that. So they never viewed the body of their

only child, never had the chance for that important rite of closure. It was only

after she was buried that they learned the truth, learned that there was only a

single, neat bullet hole in the back of Ilaria's head.

Why, her parents want to know, did the Italian government lie to them? There is

no satisfactory answer for them other than the obvious one: The government and

the military are covering up the real reasons for their daughter's death.

Giorgio and Luciana sit side by side on the couch in their apartment on the

outskirts of Rome. They hold hands, and smoke cigarettes. Giorgio is a small,

wiry 74 year-old with thick bushy eyebrows jet black hair and an intense

chiseled face. His lower lip quivers uncontrollably when he starts telling

stories about Ilaria. Luciana, 65, has short blonde hair and a solid robust

looking about her. Her voice is deep and gravelly.

Georgio and Luciana live in the apartment where Ilaria grew up. Her room is more

or less as she left it, even though she'd moved out, gone to college, lived in

Egypt for two and a half years and then gotten her own apartment in with a

friend in Rome after being hired by RAI, the Italian state broadcasting

corporation. There are photos of her everywhere. Several show her wearing a red,

hooded jacket, her blonde hair tied in a pony tail. She clutches a microphone

and peers into the camera. The reports she sent back were saved on videotapes

stacked beside the Alpis' television.

Her parents admit that they may have been overprotective of Ilaria, who as a

child was quiet and fragile. They speculate that Ilaria set out for remote areas

of the world in part to get away from their influcence, to proclaim her

independence. Giorgio tells about how young Ilaria was too shy to even ask for

what she wanted in Rome's coffee bars. "Papa, tell them I want a glass of

water," she would say. When she was 13, Ilaria worked on her school newspaper

and decided she wanted to be a journalist. Giorgio bought her a present, a small

tape recorder. As he tells this story he begins to sob uncontrollably. Luciana's

eyes turn red, and she comforts her husband. Shy Ilaria took the tape recorder

and went out into the neighborhood interviewing news vendors about their

business. It was a pattern that seemed to hold in her adult life. She struck

those who met her as sweet and reserved. But as soon as she had a microphone and

camera with her she was aggressive, professional, and self assured. "So self

assured that she didn't have to be a bitch," was how one senior military

official compared her to other female reporters.

While many television reporters saw themselves as the stars of their shows,

Ilaria once complained to her editor in Rome that she wanted to spend less time

on camera. "Why should the viewers be looking at me when I could be showing them

another ten seconds of Somalia?"

Her parents and I watch some video of Ilaria, particularly her last interview

with a clan leader named Boqor (King) Musa. Ilaria is interviewing Musa in the

town of Bosasso, a relatively peaceful port 1,500 miles north of Mogadishu on

the Gulf of Aden. Musa has a thick gray beard and a lazy eye. Everyone knows him

affectionately by his nickname, King Kong.

Giorgio Alpi turns to me and asks if I know King Kong, and if so, what I think

of him. I tell him that the King is a decent fellow who spends his days at a

hotel in Bosasso watching CNN. In these days of warlords he doesn't wield a lot

of power, but he knows what's going on. Ilaria's discussion with King Kong is

fairly mundane. They're talking about development projects and the like. Then

she brings up the subject of arms trafficking. King Kong hesitates, and Ilaria

tells Miran to shut the camera off. With the camera pointing away, but the sound

still rolling you can hear King Kong speak about things that "came from Rome,

Brescia, or Torino." Brescia is the arms manufacturing center of Italy. Then you

can hear the final words on the tape, from King Kong: "those people have much

power, contacts". Giorgio thinks the answer to his daughter's death is in that

interview.

The one and only time I met Ilaria, she had wanted to talk to me about Bosasso,

and about King Kong. Something had disturbed her that day. What was she after?

What did she want to know? The truth is, had I talked to Ilaria that night at

The Sahafi Hotel, there wouldn't have been much I could tell her. But I might

have found it curious that an Italian journalist in Mogadishu to cover the

departure of Italian troops would have found an important reason to travel to

Bosasso where there weren't any Italians.

Ilaria was on her fifth trip to Somalia. Miran was there for the first time. The

two of them caught a UN flight to Bosasso, and apparently didn't tell anybody

they were going. Several days after they left, Italian journalists began asking

the staff of the Sahafi hotel where she was. Even the Italian ambassador to

Somalia showed up at the Sahafi wearing a flak jacket and helmet with an armed

escort inquiring about her whereabouts. The owner of the Sahafi, Mohamed Jirdeh

Hussein, found it curious that the ambassador would risk being in the streets at

that time at all. The hotel staff informed the ambassador that Ilaria had gone

to Bosasso.

She was due to arrive back in Mogadishu on Saturday, March 20. The Italian

military actually sent a few men to meet her plane and escort her from the

airfield. They were going to advise her to spend the night on the Italian naval

vessel, the Garibaldi, which was anchored off of Mogadishu. (I smiled when I

first heard this. In a million years, even if we were under bombardment, the

U.S. military would never send an escort for a journalist. And most U.S.

journalists wouldn't have accepted one. We kept our distance from the military,

maintained our independence. But the Italians felt they were all in it

together.) Her plane arrived a day late, on Sunday at about 12:30. Though her

escorts could easily have found out that the flight had been rescheduled, no one

was there to meet her. So she and Miran caught a lift to the Sahafi where they

checked in and had lunch. It was just after lunch when she and I spoke.

Ilaria then phoned RAI in Rome and asked for some satellite time at around 7:00

p.m. so she could feed some video back. She said she had some good footage. "We

can speak about the story of the day later." The producer remembers that Ilaria

had something she really wanted to do. "I'm in a hurry," she said. She then

phoned her mother one last time.

At about 2:45 Ilaria and Miran left the Sahafi, heading across the Green Line

into North Mogadishu to the Amana Hotel where some Italian journalists sometimes

stayed. During the peacekeeping operation a feud had opened up between the

Italian contingent on one side and the U.S. and UN on the other. In short, the

Italians felt that they had been dissed in Somalia. This was, after all, their

former colony. They had a 100-year relationship with the place. But Operation

Restore Hope was at its core an American show. The top UN official was a former

U.S. Navy Admiral. The UN headquarters was located in the former U.S. embassy

compound south of the Green Line in territory that was controlled by warlord

Mohamed Farah Aidid. The Italians sequestered themselves north of the Green Line

in the area where the former Italian Embassy was and which was controlled by

warlord Ali Mahdi Mohamed. There they pouted and sulked and took more than a

little delight in the problems that the Americans later encountered in the

ill-fated hunt for Aidid.

The Italian peacekeeping strategy in Somalia - as it had been in Lebanon before

-was to make friends with everyone and stay out of the line of fire. I recall

standing with some Italian soldiers one day by the Green Line, surrounded by

rubble and barbed wire. The Italian commander warned me to move on because, he

said, there had been a sniper in one of the buildings who was shooting at

people. Why aren't you afraid, I asked him. We have an arrangement with him, the

commander said. So the Italians made their separate peace with the forces that

controlled the North.

Part of that dynamic involved the man everyone knew as Giancarlo. Giancarlo

Marocchino, an Italian citizen and 50-something trucking magnate from Genoa who

had made his home in Mogadishu since 1984 when he went into exile after being

indicted for tax evasion. He married a Somali woman from the clan that now

controls north Mogadishu, and settled in. If Giancarlo were to set foot in Italy

today he would be arrested, but in north Mogadishu he became a good friend to,

and important source of intelligence for, the Italian military. The U.S.

military, on the other hand, once, briefly, had him thrown out of Somalia. U.S.

intelligence was sure that Giancarlo was getting rich selling guns to the

warlords. At one point an American intelligence officer suspected that weapons

confiscated by the Italian military were sold to Giancarlo who then

reconditioned them and sold them back on the streets.

During the 1980s, Italy's socialists under Prime Minister Bettino Craxi

seemingly turned their entire government apparatus into a huge money laundering

operation - and their former colony of Somalia played a huge role in that

corruption. Trillions of lire were sent to the impoverished country as "aid" and

recycled back into the pockets of Italian government officials and their

cronies. (Some of this corruption came to light in 1989 when Mohamed Farah Aidid

- not yet a world famous warlord - sued Craxi for 50 million lire that he says

he was promised as part of a kickback scheme.) The biggest scam aid projects in

Somalia were in the northeast, near Bosasso. One of those projects involved the

construction a first-rate highway built through the desert linking Bosasso to

Somalia's main road. One of the main beneficiaries of that road, and of the

slush fund around the project, was the man who was very active in the area's

trucking business, Giancarlo Marocchino.

During Operation Restore Hope, Giancarlo became a good friend to the Italian

journalists, many of whom stayed in his home and paid for his protection.

Giancarlo provided them with meals, cars, drivers, and bodyguards. Several of

the Italian journalists, however, refused to stay with him. One of those

journalists was Ilaria Alpi. She thought he was a gun-running sleaze bag.

So Ilaria and Miran headed north over the Green Line in their white pickup

truck. Their driver was named Ali and their bodyguard was a young kid named

Mahamoud. In retrospect, it clearly wasn't advisable to be traveling around

Mogadishu with only one gunman. At that time I was traveling with two, some days

with more. I rode in a sedan and had a pickup truck full of gunners following

me. Other journalists did likewise. We realized that the pullout of the Western

troops was making Somalis nervous.

While the public in Europe and the U.S. saw Operation Restore Hope as a grand

charitable gesture, the Somalis saw the thing in terms of money. The UN, the

charities and the press were pumping hundreds of thousands of dollars a day,

cash, American dollars, into the Mogadishu economy. The foreigners living in

Somalia had hired guards and drivers and rented houses and cars for astronomical

amounts of money. Each journalist had an entire crew on his payroll. In

addition, the presence of the peacekeeping troops meant that Somali businessmen

could continue to operate. Somalia under the protection of the UN, but without

governmental authority, had become a haven for smugglers. Cigarettes, for

example were imported tax free (who was going to collect?) and sent across the

borders to Kenya and Ethiopia.

And foreign boats came to fish Somalia's waters. Sometimes warlords were able to

extract tribute from them. Sometimes they just seized the ships. At the time

Ilaria was in Bosasso, the local militia had hijacked several fishing ships that

were being held for ransom just off the coast. One ship in particular had

attracted some attention at that time. It was a ship that had been donated as

Italian aid to the Somalis. It had an Italian captain, two Italian officers and

a Somali crew. Kidnapping and hijacking were business as usual in Somalia.

With the peacekeepers pulling out Somalis were aware that everything could

change. And we were aware that the end of the gravy train might be the beginning

of trouble.

People who knew Ilaria well said that she might have become too comfortable in

Mogadishu. She was well known and popular among the Somali people, especially

the women who she spent time with and whose causes she championed. They had

given her a nickname (everyone in Somalia had a nickname), which translated to

"little smile." One of those causes was female genital mutilation. Somali girls

when they reach puberty undergo the rite of infibulation. Their labia are sliced

off and their vaginas are sewn up until their wedding night when their husbands

will crack the seal that guarantees he's getting a virgin. As horrible as this

is, few members of the highly cynical Africa journalists corps thought it worth

reporting on. The custom is common enough in Africa and it's not news. It was

news to Ilaria, who was outraged and was naive enough, or idealistic enough, to

think that journalism could somehow make life better.

At about 3 p.m. Ilaria and Miran arrived at the Amana hotel where the

correspondent for the Italian news agency (ANSA) was staying even though she

knew he wouldn't be there. The Amana is located on a hillside on a quiet street

near the former Italian embassy. Ali and Mohamoud turned the truck around so it

was pointing back down the hill where they had come from. Across the street from

the hotel was tea stall, which was just a few benches in the shade where a woman

boiled tea on an open fire. A group of men in a blue Land Rover pulled up,

parked, and began drinking tea. They never got to finish it.

Only minutes after they went in, Ilaria and Miran walked out of the hotel,

climbed into their pickup and started down the hill. The seven men from the Land

Rover, quickly put their tea down, piled back into their vehicle and overtook

the pickup, cutting them off at the bottom of the hill where the street

intersected with a main road. Two men jumped out of the Land Cruiser. And the

shooting began.

That point is where all agreement about what happened ends and where

contradictory stories, some from the same witnesses begin.

Part III: Coverup

Dominico Vulpiani tears a sheet from his memo pad and sketches a map for me. He

draws a road and two small rectangles to indicate vehicles. Then he draws little

circles in the rectangles to show where everyone was sitting: Miran in the front

seat with the driver, Ilaria in the back behind Miran, the bodyguard, Mahamoud

standing in the back of the pickup. Vulpiani looks like a goofy Jack Webb. He's

got the black buzz cut, a bit of girth that he carries well and slightly crooked

teeth. He's the director of D.I.G.O.S. The Division of Investigations and

Special Operations of the Questura Di Roma, the Italian police. He has been

supervising the police investigations into Ilaria's death for two years. Though

he's never been to Mogadishu, and none of his men have ever been to Mogadishu,

they have interviewed witnesses who have. It's clear however that Vulpiani and

his men have a big problem: Four years after the fact, with no forensic

evidence, and no reliable witnesses they can never solve this case. At best,

they can make it go away, which is what they seem intent on doing.

There are two ways to do an investigation, Vulpiani lectures. You can start off

asking why she was killed and then try to figure out who killed her. Or you can

just look at the evidence, just the facts, (he actually says, "just the facts")

and determine who killed her and then try to figure out why. You can dismiss the

parents, he says. They have taken the first approach. His office, he says, has

chosen the second.

The police, he tells me, have a witness to the shooting. He's a young guy who

goes by the name Jelle. Jelle turned up when the Italian government in 1977,

under pressure to investigate the torture charges and solve the Ilaria case sent

a special envoy, Ambassador Giuseppi Cassini, to Mogadishu. Cassini found Jelle

during one of his investigative trips to Mogadishu. On the day Ilaria was

killed, Jelle was apparently hanging around outside the Amana hotel looking for

work with any journalist who might come by.

According to Jelle, once Ilaria's pickup had been cut off, and the two men

jumped out of the car, Ilaria's bodyguard Mohamoud started firing while Ali put

the car in reverse and eventually backed into a wall because he was keeping his

head down and not seeing where he was going. Jelle said that the men in the blue

Land Rover fired all of their shots from 20 to 30 meters away. Security guards

from the Amana hotel, hearing the shooting, came out, and fired on the attackers

driving them away. The attackers then fled. One of them was killed. Ilaria and

Miran must have been shot with rounds from an AK 47 from a distance. It was a

botched robbery or kidnapping, a case of microcriminality, Vulpiani says.

Vulpiani also tells me that he heard that Ilaria's body guard fired first,

turning what might have been a simple robbery into a double murder. I had heard

that as well on the night of the killing. According to the first information I

had, Mahamoud, Ilaria's bodyguard panicked when the car was cut off and began to

fire at the attackers. He only had seven rounds in his rifle and quickly ran out

of ammunition. He then jumped out of the truck and fled on foot. Vulpiani seemed

delighted to hear this. It fit nicely into the theory that it was a botched

robbery. Mahamoud, I knew, was capable extreme panic. Nine months earlier I had

been with him when he had panicked and fired first. Perhaps luckily for me, he

had fired at American soldiers who were polite enough to aim over our heads when

they fired back.

But, I continued, it would seem to me that if Mahamoud was firing at the

attackers, they would fire back at Mahamoud, not at the unarmed passengers in

the car. Vulpiani doesn't have an answer.

Ambassador Cassini joins us in Vulpiani's office while we're talking. He's been

very helpful to me in Rome, and checks with me constantly to see how the story

is coming. Cassini says that Jelle identified Hashi Omar Hassan, they guy who's

now imprisoned in Rome, as someone who was in the Land Rover that ambushed

Ilaria. According to Jelle, Hashi didn't fire. Jelle also said he later asked

Hashi why he and his friends had attacked the journalists. Hashi is said to have

replied that it was a robbery attempt.

And where is Jelle now?

Well, there was a slight problem with Jelle, Vulpiani said. On Christmas eve of

1997 before he was supposed to testify against Hashi, he disappeared. "We

believe he's working as a mechanic in Germany." Hashi, on the other hand, was

still in jail.

I paused after listening to their story. It made so little sense on so many

levels. I've seen people hit in the head with a round from AK47 or M-16 assault

rifle before. The high velocity bullet enters the skull and the body is snapped

like a whip. The entrance wound is small, but the exit wound is another matter.

The shell entering the skull flattens and turns and it carves a bulldozer path

through the head. The exit wound explodes, spraying skull, hair and brain

matter. That's not what Ilaria looked like.

It seems to me, I said, that determining what kind of bullet hit her would be

the easiest part of this case, certainly more reliable than a witness like Jelle

who just might have been looking for a ticket out of Somalia. Incredibly, no

autopsy was done on Ilaria immediately after she was shot. Photos were taken of

her body by a medical doctor aboard the Garibaldi. But those photos and the

medical report, like so other things in this case, have disappeared. The medical

officer who wrote the report, told Ilaria's parents that it appeared to him that

Ilaria had been assassinated.

Ilaria's body was exhumed twice for autopsies. The first one was inconclusive.

The most recent, in January of 1998 concluded that Ilaria was shot at close

range, that when she was shot, she had curled up in the back seat of the truck

and placed her hands over the back of her head, that the bullet took off the

small finger of her right hand. The autopsy team consisted of six doctors, three

chosen by Ilaria's parents, three by the police. The report is very clear. But

the policemen in the room where I was sitting said simply that they didn't

believe it, didn't believe the report because it contradicted their witnesses.

Perhaps the bullet had slowed down because it went through the windshield,

someone offered. That didn't make much sense, either. Though passing through

glass and other material might slow a high velocity round it will also make it

begin to wobble or tumble. If the bullet had passed through the windshield

Ilaria would not have had a clean entry wound. The police would not accept what

their own forensic report said. It was a clean shot to the head that didn't pass

through anything. [Expert confirmation TK]

As for the robbery or kidnapping theories, whoever was close enough to shoot

Ilaria would have been close enough to accomplish any of those tasks, which they

didn't. Nothing was taken from the car.

In Mogadishu, everyone knows everyone, especially when cars are involved. I

would drive around town with my crew and Osman, my driver, would know who owned

every vehicle on the road. He could tell from 100 feet away when an approaching

car was possible trouble. The guys I travelled with could eyeball almost anyone

in the city and link him via three or four degrees of separation to someone else

who could then be identified as friend or foe. In a city where everyone was

armed and loyalties were divided along the lines of extended families, survival

depended on that kind of information.

It is impossible that no one knew who owned the blue Land Rover, not a common

vehicle in Mog. It's not likely that no one could identify any one of the seven

gunmen. Ilaria's bodyguard and driver maintained for years that they had no idea

who the killers were. Ali, Ilaria's driver, testified as much the first time he

was brought to Rome. After Jelle disappeared, Ali was brought back, given asylum

in Italy and he suddenly remembered that Hashi had indeed been in the car.

My first instinct upon hearing this, however, was that it proved that Hashi had

in fact not been in the car. It was always my experience that whenever a crime

was committed in Mogadishu, if the people in power wanted to find out who did

it, all they had to do was spread the word. The criminals generally turned up.

Obviously, no one wanted to solve this one. And since her killers were lolling

about at a tea stand in plain view, in front of Ilaria's driver and bodyguard

whom they made no effort to kill, driving a vehicle that would have been easily

identified, they obviously thought there was no reason to protect themselves.

It's very clear that the people who killed Ilaria and Miran had some very

powerful connections, and nobody is about to turn them in.

The Italian laws governing "institutional secrets" prevented me from speaking

with Omar Hashi, but I did speak to his lawyer, Douglas Duale. Duale's is a

tall, thin, immaculately dressed ethnic Somali with a tight gray beard. From his

office you can see the Basilica of St. Peter's. The walls are covered with

reproductions of Italian Renaissance art. Duale emphasizes immediately that he

is more Italian than Somali. In fact, he was born in Ethiopia and has spent most

of his life in Italy and Europe. The first thing he does is open a bottle of

champagne and he will keep my glass full and bubbling for the duration of our

four-hour discussion.

I'm a bit wary at the beginning our meeting because of what I've been told about

him. Both Cassini and Vulpiani described an insane man who made no sense, so I

almost expect him to start blubbering madly. After I arrived in Rome I asked

Cassini several times for Duale's contact number. But every time he dismissed me

saying that I really didn't want to talk to him.

Duale, however, though slightly eccentric, seems about as crazy as F. Lee

Bailey. His speech is measured and careful. Duale represents both Hashi and

Boqor "King Kong" Musa. While Musa is in the port town of Bosasso, he has come

under some scrutiny since he was the last person Ilaria interviewed.

According to Duale, Hashi was among a group of 19 Somalis detained by Italian

soldiers at the old port in North Mogadishu. As Hashi tells it, he and 18 others

had hoods placed on their heads, had their hands behind their backs and were

thrown into the harbor. Hashi and one other were able to pull a Houdini act and

wriggle free, but 17 of the prisoners died. Duale is convinced of the

truthfulness of this story from his client.

When I respond with skepticism to Hashi's entire story, Duale becomes indignant.

During the Operation Restore Hope he tells me, Somalis accused Canadian,

Belgian, and Italian Soldiers of committing atrocities. The Canadian special

forces tortured a young Somali boy to death. Nobody would have believed the

Somalis' claims except that in each case the soldiers took photographs and wrote

letters and diaries documenting the atrocities. If it wasn't for the evidence

those soldiers provided against themselves, no one would have believed the

Somali victims. He has a point - but he hasn't proven one.

The upshot of Hashi's version of events is this: In Mogadishu, Cassini, Jelle,

and a few other Somalis working with Cassini approached him with a deal. If he

went to Rome and testified that he had been abused by Italian soldiers he would

be compensated with a lot of money. All he would have to do is then testify that

as far as he knew, most of the other abuse complaints on file were false. He

would also have to testify that he was in the blue Land Rover, that he didn't

actually fire a gun himself, and the motive in attacking Ilaria's car was

robbery.

We're at the end of the evening and at the end of the champagne. "The killing of

Ilaria Alpi was entirely an Italian affair," Duale concludes. "It was a hit."

Mogadisho...

Part IV: What the Bogor Said

It's late in the evening when I leave Duale's office. A light mist falling on

Rome. I'm buzzed from the champagne and everything seems to be glittering. I

decide to walk for a bit through the city, but then I recall that at one point

during the interview Duale looked at me and said, "these people will kill to

stop the truth from coming out." I gaze at the lights on the piazza. This is

Rome. Europe. It's not Mogadishu. I decide to take a cab back to my hotel.

The headquarters of RAI just outside of Rome has all the charm of a maximum

security prison. A series rectangular concrete structures are surrounded by

high, electrified, barbed wire fence. Along one of those fences, on the outside,

is a street called via Ilaria Alpi.

Ilaria worked at RAI-3, in the news division, which is known as Tg3

(Telegiornale 3). It was her dream job. Each of Italy's television stations has

a political heritage. Raiuno, Raidue and Raitre, were controlled at one time by

the Christian Democrats, the Socialists and the Communists respectively. Raitre

was the smallest with the fewest resources. In 1987 a man named Sandro Curzi was

put in charge of Tg3. Curzi was a well known leftist commentator in Italy and

something of a hero to Ilaria. He wanted to build Tg3 as a more even-handed

professional news organization, an organization made up of young aggressive

reporters who would do with their legs what the station didn't have the money to

do.

Curzi told me that he thought most Italian journalists were lazy and cowardly,

that they practiced Grand Hotel journalism when they were abroad, and were

satisfied to read wire copy when they were home. Ilaria was everything that

Curzi wanted in a reporter. He had left Tg3 by the time she went to Somalia, but

the new directors of the organization maintained the high opinion they had of

Ilaria. Her life and death are still a palpable presence in the halls of Tg3.

Her colleagues will drop anything to spend some time talking about her.

One of RAI's journalists, Maurizio Torrealta is writing a book about Ilaria's

case. Like her parents, he believes that the key is in the final interview with

King Kong. And he thinks it has something to do with the fishing boats that were

hijacked off the coast of Bosasso.

When I met Torrealta he was carrying fat books full of official testimony about

the Ilaria Alpi case and the abuse and torture cases. In part of that testimony,

General Fiore, Italy's last commander in Somalia says that his staff had plans

for a military intervention to recapture the fishing boats. We both agree that

this attention to some hijacked boats was strange; boats were hijacked all the

time off the Somali coast.

The faction leaders who controlled Bosasso had an arrangement with the local

militia. In exchange for their "defense" of territorial fishing waters they are

allowed to make their own deals and demands with the companies operating the

hijacked boats. At the time, King Kong was negotiating the ransom that would be

paid for the ship.

Torrealta went back to interview King Kong recently and asked him if he was

afraid to talk about the situation with the fishing boat. Yes, he answered.

"Because I know that in general, those companies involved in the fishing

industry are also involved in other activities - especially those with Italian

interests," he said. Torrealta asks King Kong if he told Ilaria anything

specific. King Kong hesitates; then says "I can't say.....I don't know."

Torrealta pressed him harder: Is it possible Ilaria was killed because she knew

there were arms aboard that ship?

This time King Kong answers, "It is quite possible, because it is evident those

ships carried military equipment for different factions involved in the civil

war."

After Ilaria and Miran's death, some of their colleagues came to the Sahafi

Hotel and took her things away. They packed her TV equipment and her notebooks.

They took cash out of her duffel to pay the hotel bill. An inventory of her

possessions was taken onboard the Italian naval vessel, the Garibaldi. That

inventory included all of her notebooks, but not her missing camera. Then her

body was helicoptered back to the American morgue in Mogadishu, which had

refrigerators.

The following morning a brief ceremony took place. The metal caskets were draped

with Italian flags; they received the military honors in the presence of the

Italian ambassador, the military chaplain, General Fiore and other officers. The

bodies were flown on a G-222 transport plane to Luxor. In Luxor the coffins were

switched to a DC-9 sent by the Italian government and proceeded to Rome.

Sandro Curzi and others who knew Ilaria's work habits said that she was a

scrupulous note-taker. Somewhere between Luxor and Rome the notebooks were

taken. On board the plane were members of the Italian military, journalists from

Tg3, RAI's general manager, Italian secret service, and members of the

diplomatic corps. None of those people was ever interrogated. Things, after all,

do get lost.

The last thing that Giorgio Alpi said to me when I left his apartment was that

he now suspected Giancarlo Marocchino was somehow behind his daughter's death.

Back home in New York, I watch Carlos' video over and over again of Giancarlo

supervising the extraction of Ilaria's and Miran's bodies from the Toyota

pickup. He was the first person on the scene, which is not surprising. North

Mogadishu was his turf. And it's also not surprising that he looks unruffled.

Death was a way of life in Mogadishu. Then Giancarlo says to the camera, "They

were somewhere they shouldn't have been." And I wonder if I'm listening to

Giancarlo, the protector of Italian journalists commenting that Ilaria should

have been using his bodyguards and cars, or if I'm listening to Giancarlo the

gunrunner saying that Ilaria shouldn't have been asking questions about fishing

boats in Bosasso. Suddenly I'm aware that this particular street in Mogadishu

never seemed that dangerous to me. I had driven down it dozens of times before

and never given it a second thought. I returned the day after Ilaria's death,

and many times after, feeling perfectly safe and in control.

SOURCE:

http://www.raffaeleciriello.com/site/pw/sto/39.ilaria.maren.html